Part 3: The Complex History of Islamic Extremism and Russia's Contribution to the Rise of Al Qaeda and ISIS

The Soviet coup d'etat and invasion of Afghanistan captures the attention of a young Osama bin Laden.

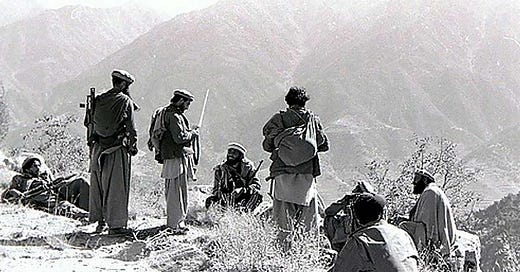

Mujahideen fighters relax in the mountains of Afghanistan

This is part three of a multi-report series that explains the rise of modern Islamic extremism. From 1951 to 2021, a series of key geopolitical events, many independent of each other, caused the Islamic Revolution, the rise of Al Qaeda and ISIS, the creation and collapse of the caliphate, and the reconstitution of ISIS as the ISKP. While Western influence and diplomatic blunders are well-documented throughout this period, the Soviet Union and the Russian Federation are equally culpable. The editors would like to note that a vast majority of the 1.8 billion people who are adherents to some form of Islam are peaceful and reject all forms of religious violence.

The Kremlin fears the spread of radical fundamentalist Islam

On December 5, 1978, the Soviet Union and Afghanistan signed a 20-year “friendship treaty.” Moscow saw stable relations with Afghanistan as a key national security issue and had worked to improve bilateral relations since the end of World War II. The agreement included economic and military assistance and was intended to prop up the new government of Nur Muhammad Taraki following a violent coup d’état.

Just as Western intelligence had failed to detect the coming Iranian Revolution, their Soviet counterparts failed to warn the Kremlin of the April 1978 Suar Revolution in Afghanistan, which overthrew President Sardar Mohammed Daoud. Daoud had come to power in a 1973 coup and was executed, as were over 2,000 military and government officials.

Hafizullah Amin and Taraki of the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan led the brutal takeover and ended the 152-year Barakzai Dynasty. Taraki was named Chairman of the Council of Ministers, the de facto leader of Afghanistan, and replaced the single-party rule of Daoud with the single-party rule of the Communist Party. Initially, Amin and Taraki were aligned, but within a year, their relationship had turned hostile as Taraki made a series of politically and religiously unpopular decisions, and Soviet influence evolved into direct interference.

By March 1979, just two months after the Shah of Iran abdicated, 25 of the 28 Afghan states were no longer considered safe. The new government was already unraveling, with Amin tugging at the threads. He maneuvered the Afghan Politburo to name him Prime Minister, eroding Chairman Taraki’s power.

Moscow saw Amin as a threat who leaned toward Pakistan, China, and the United States, with KGB operatives believing he was working with the CIA. As Prime Minister, Amin instituted extreme repression within Afghanistan in an attempt to stem protests and growing antigovernment violence. By July 1979, Soviet-controlled media were publicly declaring their non-support for Amin’s leadership.

Behind closed doors, the Kremlin was unimpressed with Amin and Taraki, believing that neither was capable of maintaining power. Moscow became increasingly worried that the Islamic Revolution in Iran could spread to the Muslim-dominated Caucasus and the southern Soviet republics. Soviet General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev’s advisors were trying to convince him that intervention in Afghanistan would be necessary to prevent a similar revolution from occurring in Central Asia and then spreading throughout the Russian state.

In June 1979, the first Soviet troops entered Afghanistan at Kabul’s request. The arrival of military equipment, including T-72 tanks and infantry fighting vehicles, occurred openly, but the Soviet Union employed the 'little green men' approach with its troops. A battalion of “unarmed” airborne soldiers (VDV) was deployed as “specialists and advisors.” A month later, Kabul requested two additional Soviet divisions, which Moscow declined.

In the next four months, 160,000 Afghans fled to Pakistan to escape the growing political and religious violence. Despite a strained relationship with President Jimmy Carter’s administration, Pakistani leaders appealed for the U.S. to intervene indirectly by providing support to a growing number of Afghan Islamist rebels. Within the halls of Washington, D.C., the Domino Theory, popularized in the 1950s and 1960s, still guided foreign policy. There were concerns that if the Soviet Union occupied Afghanistan, communism could spread to other nations.

Despite their misgivings about Taraki’s ability to rule, Moscow backed him in an attempt to remove Amin as Prime Minister. Amin was invited to Moscow in September, and after returning to Kabul on September 11, 1979, Taraki invited him to a meeting on September 13. Amin refused but ultimately bowed to Kremlin pressure. Arriving on September 14, Amin barely escaped a Kremlin-backed assassination attempt. Diplomatically, the plan backfired, with the Afghanistan military rallying around Amin.

Taraki was arrested under the order of Amin, and the Kremlin considered a rescue plan but concluded that Afghanistan’s military leadership had coalesced around Amin. During a phone call on October 8 with Brezhnev, Amin inquired about his next steps regarding Taraki, and was told the decision was his to make. On the same day, Taraki was murdered by suffocation, and Amin believed that he had secured control of Afghanistan.

The Kremlin wasn’t being completely paranoid as they discussed how Amin was leaning toward the West. On October 15, Amin reached out to the U.S. State Department, stating he was interested in speaking to anyone at the U.S. mission. The interim Chargé d’Affaires to Afghanistan, James Bruce Amstutz, advised Washington not to have further discussions with Amin. He cited the murder of Taraki, rifts within the Afghanistan military, the crumbling security situation, the ongoing executions of political rivals, and the dangers of how the Kremlin could respond.

Amstutz’s warnings were ignored, and on October 27, Amin had a 40-minute meeting with U.S. diplomat Archer Blood. The meeting was uneventful, with Amin expressing his desire to improve U.S.-Afghanistan relations and attempting to make a case for receiving foreign aid. Blood expressed Washington’s concern about Kabul’s lack of attention to poppy growers and the drug trade, anti-West rhetoric, and the ongoing government-sanctioned violence. The meeting was not kept secret from the Soviets and was the leading news story in Afghanistan on the same day.

For KGB leader Yury Andropov, this was a bridge too far and only confirmed his belief that Amin was a U.S. foreign agent. Just as the U.K. had convinced the U.S. in 1953 that Iran would lean toward Moscow, Andropov convinced Brezhnev that Afghanistan was ready to lean toward Washington. This was an unacceptable national security threat to the Soviet state.

The Kremlin started to set conditions for a coup and the invasion of Afghanistan. On December 13, the KGB attempted to poison Amin and, days later, attempted to assassinate him. On Christmas Day, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan, which Amin believed was meant to restore order and cement his control of the nation. A second Soviet attempt to poison him on December 26 also failed. Finally, on December 27, Soviet troops attacked the Presidential Palace, and Amin was killed by gunfire, believing up to the last moment, the troops had come to secure his position.

The Soviet invasion and violent overthrow of Amin shocked the world. The United States, Pakistan, and China condemned the aggression. Pakistan worried that after pacifying Afghanistan, the Soviets would invade their country to reach the Indian Ocean and establish warm water naval ports. China accused the Soviet Union of wanton expansionism and warned other developing nations that continued relationships with Moscow would lead to a similar fate.

The Soviet Union installed Babrak Karmal as a puppet leader. Days later, Karmal declared that Amin was a conspirator, criminal, and a spy of the United States. In neighboring Pakistan, the radicalization of a Saudi heir to a construction fortune, Osama bin Laden, was about to begin.

Malcontent News is an independent news agency established in 2016 and a Google News affiliate. To remain independent, we are supported by our subscribers and limit advertising. The easiest way to support our team is to subscribe to our Substack.

Coming Up Next, Part 4: Osama bin Laden joins the fight against the Soviet Union while Iranian leader Ayatollah Khomeini directs his rhetoric towards Iraq, setting off alarm bells in Iraq.

Moscow's strategic objective of controlling Afghanistan was direct access to the indian ocean via Pakistan.

Yeah, if they didn’t have nuclear weapons. Unlike Ukraine, they did Not give up their 90+ nuclear weapons because the US and UK guaranteed their safety from invasion by russia in 1994.

Pootyboy will never step in that direction because he’s terrified of death like most all russians. Just factual reality.