Part 5: The Complex History of Islamic Extremism and Russia's Contribution to the Rise of Al Qaeda and ISIS

The Iranian Revolution contributed to the Soviet Union's decision to invade Afghanistan. It also was the spark that started the Iran-Iraq War and the rise of Saddam Hussein.

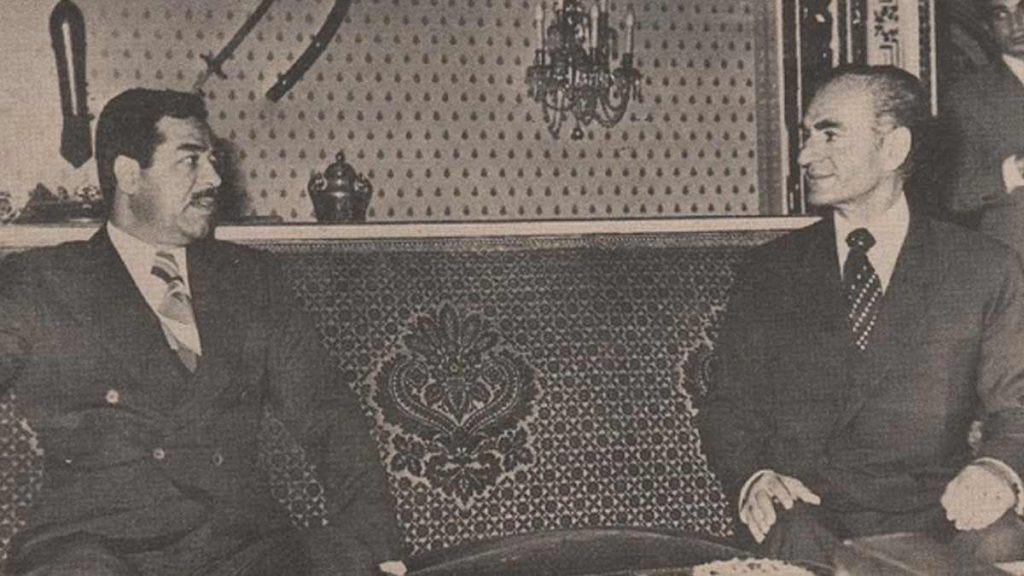

Vice President of Iraq Saddam Hussein (L) and Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, better known as the Shah of Iran (R), during the Algiers Agreement meetings in 1975

Credit – Photographer unknown – public domain

This is part five of a multi-report series that explains the rise of modern Islamic extremism. From 1951 to 2021, a series of key geopolitical events, many independent of each other, caused the Islamic Revolution, the rise of Al Qaeda and ISIS, the creation and collapse of the caliphate, and the reconstitution of ISIS as the ISKP. While Western influence and diplomatic blunders are well-documented throughout this period, the Soviet Union and the Russian Federation are equally culpable. The editors would like to note that a vast majority of the 1.8 billion people who are adherents to some form of Islam are peaceful and reject all forms of religious violence.

If you missed the previous installment, part four is available.

Part 4: The Complex History of Islamic Extremism and Russia's Contribution to the Rise of Al Qaeda and ISIS

Mujahideen fighters relax in the mountains of Afghanistan

The rise of Saddam Hussein and the start of the Iran-Iraq War

The Soviet Union had limited influence over Iraq's internal politics during the Cold War. However, the rise of Saddam Hussein and the Iran-Iraq War, followed by Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait and Operation Desert Storm, influenced geopolitics in the Middle East, the Soviet Union, Pakistan, and Afghanistan for the next three decades. Today’s installment takes a detour from the Soviet Union to provide important historical context on how Saddam Hussein came to power, and the start of the Iran-Iraq War.

During the opening decades of the Cold War, Iraq aligned itself with the Soviet Union. In 1958, Abdul Salam Arif led elements of the Iraqi army into Baghdad, contributing to the overthrow of the Hashemite Monarchy in support of Abdel Karim Qasim. After taking control, Qasim appointed Arif as the deputy prime minister, interior minister, and deputy commander-in-chief of the Iraqi armed forces.

The afterglow of the coup was short-lived, with Qasim supported by the Soviet-backed Iraqi Communist Party, and Arif supported by a coalition of Ba’athists and pan-Arabs. Arif was stripped of all his titles less than 60 days later and was sent to Germany to serve as a low-level ambassador. He rejected the position, and upon his return to Iraq, Arif was arrested, found guilty of plotting against the state, and sentenced to death. Two years later, President Qasim commuted his sentence and had him released from prison.

After his release, Arif was named the leader of the Iraqi Revolutionary Command Council and quietly regained his political clout. On February 8, 1963, Qasim was overthrown during the Iraqi Ramadan Revolution. After a brief show trial, the Ba’athists showed no mercy, issuing an immediate execution order. In a sham election, Arif was named the new president of Iraq.

As president, he once again found himself at odds with some of the groups that helped bring him to power, including the Ba’athist Party. In 1964, he declared the creation of the Arab Socialist Union, uniting with Egypt, and advocated for Arab reunification across the Middle East. To further consolidate power, Arif nationalized over 20 industries. The same year, a plot to overthrow him was exposed, resulting in the arrest of members of the Ba’athist Party, including Saddam Hussein.

Under questionable circumstances, Arif died in a plane crash on the outskirts of Baghdad on April 13, 1966. Ultimately, his brother, Abdul Rahman, was elected president by the Defense Council. Military leaders and the Ba’athists chose Rahman due to his political weakness, which would make him easy to control.

In Washington, U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson considered Rahman a political moderate whose appointment created an opportunity to improve U.S.-Iraqi relations. Johnson hoped he could draw the Middle Eastern nation away from the Soviet Union’s sphere of influence.

Diplomatic efforts would be dashed on June 5, 1967, while dialog between Baghdad and Washington was ongoing, when the Arab-Israeli Six-Day War started. In response to the U.S. backing of Israel, Rahman ended talks and severed diplomatic relations.

In Baghdad, Rahman’s political opponents used the Six-Day War as leverage to push his new government to nationalize the foreign-owned Iraq Petroleum Company so that oil could be used as an economic weapon. Behind the discord, the Arab Socialist Ba’ath Party was already plotting another coup, with Hussein, who had been released from prison, among the lead conspirators.

Rahman’s government was overthrown on July 17, 1968, in a relatively peaceful coup d’état, compared to the 1958 and 1963 coups. Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr was named the new president. After taking control, the new Ba’athist government announced that it would maintain its current relationship with the Soviet Union. The Ba’athists also wanted to expand relations with the Chinese People’s Republic, which was in the middle of the Cultural Revolution led by Chairman Mao Zedong.

In early 1969, Rahman would be charged with engaging in activities against the government. He was held for 15 months without trial and repeatedly tortured before being allowed to move to London, England, on compassionate grounds due to poor health.

Hussein’s collaboration in the coup earned him the vice presidency, and he led the full nationalization of the country’s oil industry, which was completed in 1972. When Rahman was overthrown, diplomatic relations between Iraq and Iran were poor, in large part due to Iran’s support of Iraqi Kurdish rebels. In late 1974, Hussein directed the Ba’athist government to improve relations, which led to the March 6, 1975, Algiers Agreement and two additional treaties signed later in the same year.

The Algiers Agreement aimed to settle maritime and territorial disputes in Iran’s Shatt al-Arab region and Iraq’s Khuzestan Province. Additionally, Iran agreed to end its support of the Kurdish Rebellion. After the treaty was signed, foreign relations temporarily improved, marking the end of nearly a decade of political isolation. The diplomatic success grew Hussein’s cult of personality.

A year after the Algiers Agreement, Hussein was appointed General of the Iraqi Armed Forces, while continuing to hold the office of vice president. Leveraging his status as a rising star, he initiated an aggressive military modernization program, purchasing billions of dollars' worth of hardware from the Soviet Union and France. Within 15 years, Iraq would have one of the largest conventional militaries in the world, with over 1,000 Soviet T-72 main battle tanks at its core.

Around the same time, President al-Bakr’s health began to deteriorate significantly. Behind the veil, Hussein was running a shadow presidency, controlling the economy, the military, and foreign affairs. He used that power to become a feared strongman, cultivating an inner circle of loyalists intent on taking full control of the Ba’athist Party and with it, the leadership of Iraq.

Despite declining health and weakening political power, President al-Bakr initiated negotiations for unification with Syria in 1979. If an agreement were reached, Syrian President Hafiz al-Assad would become the deputy leader of the combined nations, stripping Hussein of his power. The U.S. and Israel were also opposed to the talks, worried that a unified Syria and Iraq would further destabilize the region, creating an existential threat to Israel and further entrenching Soviet influence.

On July 16, in what could be described as a one-man coup brought on by a health crisis, Hussein forced al-Bakr to resign, becoming the President of Iraq. Syria unification talks were immediately terminated.

Despite the establishment of the Algiers Agreement and the subsequent treaties, negotiated in part by Hussein, relations between Iraq and Iran had become strained again. Iranian leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini repeatedly called for the overthrow of the Iraqi Ba’athist government in jingoistic speeches due to Iraq’s embrace of secularism. The newly minted President Hussein tried to appease Khomeini by praising the Iranian Revolution and calling for renewed Iraqi and Iranian friendship, as well as a mutual pledge to refrain from interfering in each other’s internal affairs.

Hussein’s call for better relations was hollow and fell on deaf ears in Tehran. Diplomatic relations between Iran and Iraq rapidly went from strained to crumbling. On March 8, 1980, Iran recalled its ambassador and demanded that Iraq do the same. The next day, Iraq symbolically declared Iranian Ambassador Fereydoun Adamyat persona non grata.

Before the Islamic Revolution, Iran’s GDP was the largest among the 36 U.N.-recognized Greater Middle East nations. Under the leadership of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the Shah of Iran, the country’s military expanded to over 300,000 active-duty personnel and undertook a massive modernization program. Pahlavi ordered the purchase of billions of dollars' worth of weapons from the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union, including almost 80 state-of-the-art F-14 multirole fighter planes.

One of the immediate outcomes of Khomeini’s rise to power and the Iranian Hostage Crisis was the embargo of parts, munitions, and other materials needed to maintain Iran’s military. Political purges, arrests, and executions also eliminated many skilled and loyal military officers, pushing their subordinates into hiding. The more Khomeini tightened his grip, the weaker Iran’s military became.

To deal with dissenters and political enemies, Khomeini created a personal guard, the paramilitary Islamic Revolution Guard Corps (IRGC), which would go on to be the terrorism-supporting arm of modern-day Iran. On April 30, 1980, Khomeini issued an order to establish the Organization for Mobilization of the Oppressed, more commonly known as the Basij. Often referred to as the “20 Million” during speeches, Khomeini would boast that with the Basij, no nation could defeat Iran. In reality, the all-volunteer paramilitary force was comprised of poorly trained and led men, most of whom had little education.

During the volatile first eight months of 1980, Iran and Iraq accused each other of over 1,200 border incidents, airspace violations, and maritime disputes. Hussein now viewed the Algiers Agreement as a mistake and believed he could use the post-revolution chaos in Iran to his advantage. He also saw an opportunity to engage the U.S. through the enemy of my enemy is my friend politics.

Hussein and his advisors concluded that the Iraqi military had an opportunity to quickly retake the disputed Iranian Khuzestan Province and its oil fields, thereby expanding Iraq’s access to the Persian Gulf. On September 10, using the open issues of the Algiers Agreement as a casus belli, Iraq launched a limited military operation to seize the territories of Zain al-Qaws and Saif Saad. Twelve days later, the limited operation turned into a full-scale invasion of Iran, starting an eight-year war.

Malcontent News is an independent news agency established in 2016 and a Google News affiliate. To remain independent, we are supported by our subscribers and limit advertising. The easiest way to support our team is to subscribe to our Substack.

Coming Up Next, Part 6: The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan turns into a quagmire. By 1984, Moscow was already seeking an exit strategy. The Brezhnevification of the Soviet government propelled a moderate to power. Then, in 1986, a disaster would irreversibly alter the path of the Soviet Union. Osama bin Laden didn’t see the planned Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan as the beginning of the end. He saw it as the end of the beginning.

Thanks. We need a good subtatianted research historic book on this.

This is a context for the chain reaction that led to Trumpism:

-| September 11, 1990: US military stationed near holy cities in Saudi Arabia https://millercenter.org/the-presidency/presidential-speeches/september-11-1990-address-joint-session-congress.

-> 9/11

-> Two unjustified US wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

-> Radical contraction of American freedoms, including the establishment of Homeland Security (leading to ICE).

-> Wasting of $8 trillion [Brown University 2021].

-> Devastation of morals by the baseless wars, war crimes, killing up to a million [Brown University 2021] or more.

-> Destruction of stability in the Middle East and Northern Africa, leading to wars in Syria, etc.

-> Removal of the Taliban, thus removing pressure on Russian influence in Central Asia and the Caucasus.

-> Legitimation of Putin's wars in Chechnya and his regime in general, including the use of a NATO-ISAF base and supply chains in Russia [www.themoscowtimes.com/2012/03/14/lavrov-backs-nato-using-ulyanovsk-base-a13280].

-> The two US wars destroyed adherence to international law and legality, and legitimacy in general.

-> The 2008 financial crisis, primarily caused by budgetary deficits and debts resulting from the uncontrolled military spending without increased taxes, leading to fiscal irresponsibility and a lack of fiscal regulations.

-> Historic high social income inequality (partially offset by Baby Boomers' investments at maximum rates, Millennials entering the workforce, and excessive borrowing).

-> Increased power and wealth for US oligarchy and corporations, including in 2008, further increasing inequality, compounded by Moscow's disinformation via the Internet, direct and indirect purchases of politicians, officials and influencers in the USA, Europe, UK.