Part 6: The Complex History of Islamic Extremism and Russia's Contribution to the Rise of Al Qaeda and ISIS

As the Iran-Iraq War starts, the Russo-Afghan War becomes a quagmire for the Soviet Union. Moscow looks for a way out, and Osama bin Laden prepares to take his victory lap.

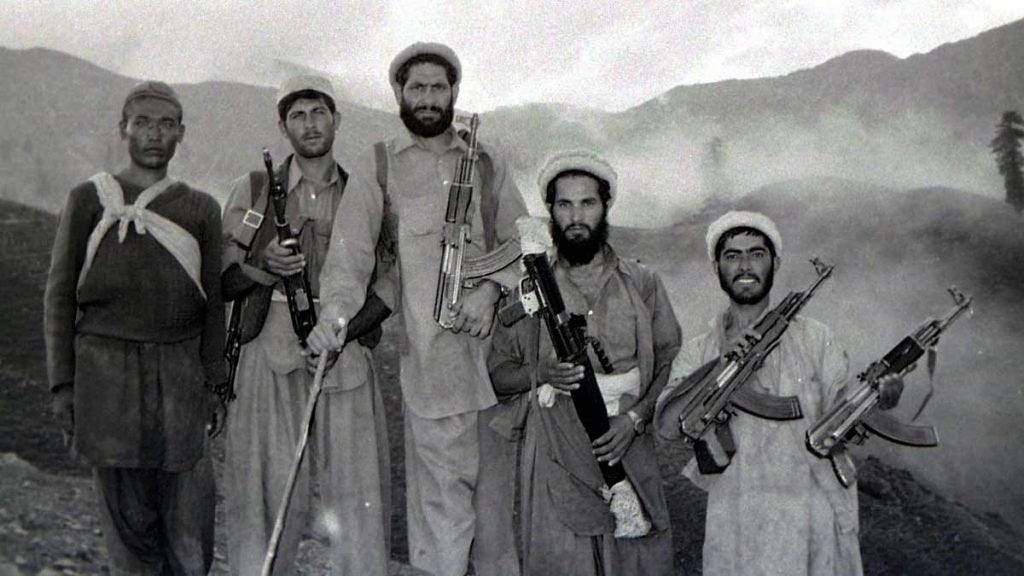

Mujahideen fighters in Afghanistan, 1985

Credit – Erwin Franzen, Creative Commons 2.0-4.0

This is part six of a multi-report series that explains the rise of modern Islamic extremism. From 1951 to 2021, a series of key geopolitical events, many independent of each other, caused the Islamic Revolution, the rise of Al Qaeda and ISIS, the creation and collapse of the caliphate, and the reconstitution of ISIS as the ISKP. While Western influence and diplomatic blunders are well-documented throughout this period, the Soviet Union and the Russian Federation are equally culpable. The editors would like to note that a vast majority of the 1.8 billion people who are adherents to some form of Islam are peaceful and reject all forms of religious violence.

If you missed the previous installment, part five is available.

Part 5: The Complex History of Islamic Extremism and Russia's Contribution to the Rise of Al Qaeda and ISIS

Vice President of Iraq Saddam Hussein (L) and Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, better known as the Shah of Iran (R), during the Algiers Agreement meetings in 1975

The Soviet Union is stuck in an Afghan quagmire of its own making

After the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan and completed its coup d’etat, Soviet troops launched a series of large-scale attacks in the central, northern, and western states of Afghanistan through 1985. While these large-scale attacks sometimes brought about temporary stability, the mujahideen would retreat into Pakistan or deep into the mountains and return as soon as the Soviets withdrew, or the winter snows melted.

Moscow had expected the Afghan army to do the majority of the fighting, with Soviet forces providing intelligence, logistics, close air support, and artillery. The opposite happened, with the local military units providing little support and frequently running from battles.

Soviet troops, supported by the KGB and Afghanistan's intelligence agency, the Khadamat-e Aetla’at-e Dawlati (KhAD), instituted brutal programs against the civilian population. The torture, rape, disappearances, and extrajudicial executions only built more support for the mujahideen, who promised protection to those who gave them shelter. That protection came at a price. A strict interpretation of Sharia Law had to be followed, and farmers grew poppies to fund the rebels through opium sales. Despite periods of intense fighting and the Soviets sending more military assets into the region, the war was essentially a stalemate.

With numerous reporters embedded with mujahadeen, popular support in the Middle East, Europe, the U.S., and China rapidly grew. The mystique of chiseled-faced tribesmen bravely fighting against Russian tanks and helicopters on horseback was embraced as a noble struggle.

The rhetoric of the Cold War peaked in 1983, with public fear of nuclear annihilation at the highest levels since the Cuban Missile Crisis. To the West, the existence of the Soviet Union was viewed as an existential threat. Moscow regarded the war in Afghanistan as a battle against Islamic extremism and an opportunity to expand its sphere of influence. In comparison, Europe and the U.S. viewed the war as an extension of the Cold War.

The Reagan administration sought to destabilize the Soviet Union economically and diplomatically as a strategy to end the Cold War without the side effects of radioactive fallout and nuclear winter. Under Reagan, the Department of Defense budget swelled to $1.45 trillion in inflation-adjusted dollars. The U.S. labeled the Soviet Union the “Great Satan.” Despite Washington’s opposition to the Islamic Revolution in Iran, the plight of outgunned Islamic militants fighting against Soviet brutality made for odd bedfellows.

By 1985, the biggest battlefield threat to the mujahideen was the Soviet Aerospace Forces. The Mi-24 Hind helicopter gunship earned a fearsome reputation, and the air force indiscriminately bombed civilians and civilian infrastructure. Refugees poured into Pakistan, creating a humanitarian crisis. The CIA advised Congress and the Department of Defense that the biggest need for the Islamic rebels was air defense.

The mujahideen and other factions aligned against the Soviets were already backed by the U.S., the United Kingdom, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and China. The CIA-run Operation Cyclone, which started in 1979 and was created to counter the Soviet Union’s war of aggression, saw its budget dramatically increased in 1986. Among the billions of dollars in military aid and equipment sent through Pakistan, supplies of Stinger antiaircraft missiles were provided to the Afghan resistance.

The Stinger offered short-range air defense (SHORAD) capabilities to the mujahideen, tipping the balance of power on the battlefield. Radicalized fighters adopted the three-man ambush tactic to down Soviet aircraft, which required two of the three Stinger operators to act as bait. By the end of the year, Russian aviation was practically grounded, and without air support, the number of Russian casualties increased significantly.

With the Soviet military stuck in a quagmire, another seemingly unrelated event would alter the course of world history. On April 26, 1986, after a failed safety test on Reactor 4 at the Chornobyl Nuclear Power Plant, technician Leonid Toptunov pushed the AZ-5 button, which was meant to scram the reactor. Instead, due to a design flaw, Reactor 4 exploded, causing the worst nuclear accident in world history. The containment and clean-up process would go on to require the near-total mobilization of the Soviet Union’s resources.

A combination of a stagnant economy that started to fail in the 1970s, the inability to keep up with Western defense spending and technology, the war in Afghanistan, and the economic cost of cleaning up the Chornobyl disaster put the Soviet Union irreversibly on the path toward collapse.

Inside the Kremlin, Mikhail Gorbachev had been seeking an exit strategy from Afghanistan since becoming the General Secretary in 1985. Gorbachev was selected to lead the Soviet Union, in part, due to his quiet opposition to the Russo-Afghan War within the Politburo, and also due to his youth.

The Russian government was stuck in a period called Brezhnevification. After Leonid Brezhnev's death on November 10, 1982, the Politburo was resistant to any further overtures to the West, despite a period of détente that began in the 1970s under U.S. President Richard Nixon.

Despite his known failing health, Yuri Andropov, the head of the KGB and an architect of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, was named Secretary General. He passed away 15 months later at age 69. Internal records show he spent his last months too ill to make any meaningful decisions. He was replaced by Konstantin Chernenko, who became General Secretary on February 13, 1984, and held the position for only 13 months, dying at the age of 73. In contrast, Gorbachev was only 54 years old. He was the first General Secretary since the death of Joseph Stalin who did not fight in World War II and had a political career that began during the Khruschev Thaw.

The metaphorical rusting of the Iron Curtain and the Glasnost programs introduced by Gorbachev permitted unprecedented public criticism of the government. The mothers of mobilized soldiers killed, wounded, and missing in Afghanistan became a powerful group with an oversized voice. Returning veterans also decried the war, confirming reports of human rights violations and atrocities against civilians. Moscow had spent centuries repressing such speech. Now it found itself ill-equipped to manage the growing outrage while maintaining its vitally needed outreach to the West.

In 1987, with popular support for the war plummeting, the Soviet government announced it would start a controlled two-year withdrawal from Afghanistan. For some, the decision brought hope of a new phase of stability, and a return to life before the Soviet invasion and the violent coups of the 1970s. However, thousands of Islamic fighters didn’t come to fight for liberation. They choose to go to Afghanistan in response to the fatwas calling for the protection of historic Islamic lands from infidel invaders. In an ironic twist, the thing Moscow feared the most, an Islamic Revolution in Afghanistan similar to the one in Iran, was starting to form.

Where was Osama bin Laden? During the first seven years of the Russo-Afghan War, he engaged in very little fighting and did not prepare or lead any strategic operations. However, bin Laden did a lot of self-promotion and leveraged his contacts within Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, and the U.S. to cultivate a carefully prepared image. For him, the Soviet withdrawal wasn’t the beginning of the end. It was the end of the beginning. What almost no one knew in 1987 is that bin Laden was laying the foundation for a new organization. He would name it al-Qaeda.

Malcontent News is an independent news agency established in 2016 and a Google News affiliate. To remain independent, we are supported by our subscribers and limit advertising. The easiest way to support our team is to subscribe to our Substack.

Coming Up Next, Part 7: One more detour to Iraq to provide additional context from 1981 to 1989. U.S. interference within the Middle East reached its apex when Washington started to worry that Iraq might achieve a strategic victory against Iran. The meddling assisted Saddam Hussein's transformation from strongman to brutal dictator. While the Russo-Afghan War was coming to an end. Hussein prepared for his next military objective.